In future, Switzerland will not be allowed to export weapons to countries where there is civil war and human rights are severely violated. Parliament has now decided this.

An end is now in sight to the heated debate on tightening the criteria for the export of Swiss war material. After the Council of States – the small chamber of the Swiss parliament – the National Council has now also spoken out in favor of restricting the export of war material. The forthcoming final vote is likely to be a mere formality. The export of weapons has long been an issue in Switzerland. However, the discussion gained momentum with the popular initiative “Against arms exports to civil war countries” – also known as the corrective initiative. The initiative was launched in November 2018 by the Alliance Against Arms Exports to Civil War Countries. The Alliance is made up of several political movements, parties, aid organizations and church representatives, including the Group for a Switzerland without an Army (GSoA), the aid organization Terre des hommes, the Social Democratic Party (SP), the Greens, the Green Liberals, the Civic Democratic Party (BDP) and the Evangelical People’s Party (EPP). The initiators are calling for the criteria for the export of weapons to be enshrined in the War Material Act and the constitution – instead of the current War Material Ordinance. The aim is to remove the government’s (Federal Council’s) sole authority to decide on the criteria for approving arms exports. By enshrining the criteria at legislative level, it should become more difficult to change the criteria: any proposed changes would have to be approved by the people. In addition, the corrective initiative calls for the relaxation of the licensing criteria for arms exports introduced in 2014 to be reversed. Under pressure from the arms industry, the government eased the export rules at the time after introducing restrictive export controls five years previously. Since 2014, Switzerland has once again been able to export weapons to countries that “systematically and seriously” violate human rights, provided there is “a low risk that the war material to be exported will be used to commit serious human rights violations”. In 2016, the government went one step further and even permitted exports to countries involved in armed conflicts, provided the conflict does not take place in the recipient country itself.

The corrective initiative quickly gained many supporters among the population. In June 2019, it was submitted with more than 134,000 signatures. That is more signatures than are required to put an issue to a vote by the population entitled to vote. It also fell well short of the 18 months required by law to collect signatures. The surprising success of the initiative forced the government to take action. In order to prevent a referendum, it responded with a counter-proposal in December 2019. In it, it declared its willingness to ban arms exports to countries where human rights are “systematically and seriously” violated. However, it called for an exemption clause: the government should be allowed to decide on arms exports itself if there were “exceptional circumstances to safeguard the country’s foreign or security policy interests”. According to the exception, deliveries to democratic states would be permitted, even if they were involved in an armed conflict. The government also rejected the idea of anchoring it in the constitution. In June, the Council of States deleted this exception and adopted the counter-proposal. The National Council has now also deleted the clause and recommended the counter-proposal for adoption by 96 votes to 91. The result is mainly due to six abstentions from the FDP, the majority of whom voted against the corrective initiative. Most of the demands of the initiators have thus been met. The Alliance Against Arms Exports to Civil War Countries has now announced that it will withdraw the initiative after parliament’s final decision and refrain from holding a referendum. Developments were on the horizon

As surprising as the National Council’s decision may be, a tightening of Swiss war material exports had been on the horizon for some time. The government felt the social pressure in 2018 in particular when it planned to further relax the licensing criteria. Arms exports to countries with an armed conflict were to become possible again “if there is no reason to believe that the war material in question will be used in this conflict”. Critics felt that this was a condition that could not possibly be monitored. In the same year, the Swiss Federal Audit Office published a report on the control of the transfer of war material. The auditors found that the export rules were already being freely interpreted and partially circumvented at the time. The report states, for example, that arms deliveries that could not be approved from Switzerland would end up in the final destination via intermediate countries. Opponents of Switzerland’s liberal arms export practices felt vindicated. The corrective initiative was launched. https://militaeraktuell.at/wie-steht-es-heute-um-den-westbalkan/ Media reports of Swiss weapons appearing in conflict zones further fuelled the debate and mobilized a broad base to support the initiative.

In 2018 and 2019, for example, it became known that Swiss-made hand grenades were used against the civilian population in Yemen, Syria and Libya. Years earlier, the RUAG armaments group had sold them to the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. At the end of 2020, the remains of a kamikaze drone labeled “Swiss made” that had been used by the Azerbaijani army were found in the Nagorno-Karabakh war zone and made headlines. The drone parts were a drive motor from Faulhaber Minimotor SA, a company based in the canton of Ticino in Italian-speaking Switzerland, which was used by Israel for the folding mechanism of the Harop drone’s wings. At the time, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (Seco), which is responsible for export controls, stated that electric motors could in principle be exported to any country without a license. However, this did not lessen the call from advocates of stricter export controls for Swiss weapons. The damage to Switzerland’s image as a humanitarian actor and guardian of human rights has already been done, critics warned. Arms industry disappointed

Swiss arms manufacturers see the risk of the Swiss arms industry being weakened by the forthcoming tightening of export practices. Representatives of the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and FDP.The Liberals argue that there is a risk of job losses and negative economic consequences for Switzerland. Industry representatives point to the importance of the defense technology industry for Swiss security policy. Switzerland needs industrial capacities in order to be able to fulfill its neutrality obligations in a sovereign manner and to avoid becoming dependent on foreign suppliers of war material. In an interview with the Swiss radio and television station SRF, Matthias Zoller from the Swiss armaments association SWISS ASD (Aeronautics, Security and Defence) explained that a strict export practice would jeopardize offset transactions. These are offset transactions in connection with arms procurement abroad, i.e. counter-transactions that a state makes with Swiss arms companies when Switzerland itself buys weapons there. One example of this is the US F-35 fighter jets, in return for which the USA invests in Swiss industry, according to Zoller. Swiss arms exports reach record high in 2020

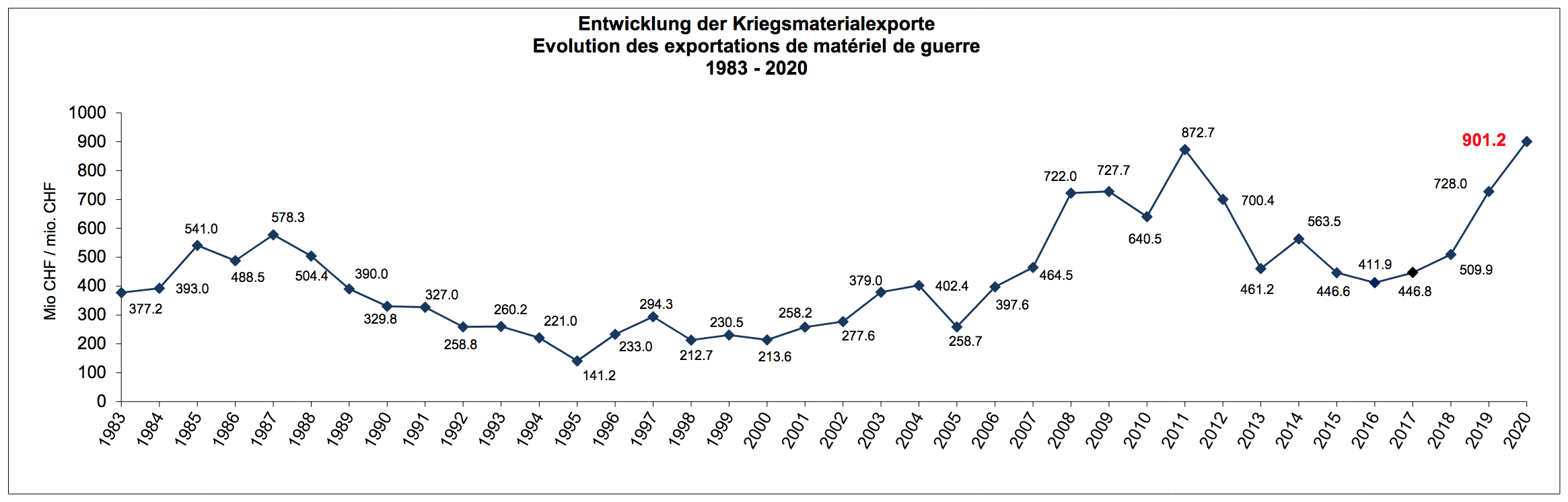

Last year, Swiss companies exported armaments worth a total of more than 900 million Swiss francs (just under 830 million euros). This is 24% more than in the previous year and 67% more than in 2018. Over a five-year period between 2016 and 2020, Switzerland ranked 14th in the world for arms exports, according to a report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Its share of global arms exports was therefore 0.7 percent. The USA takes first place on the list, followed by Russia, France, Germany and China. Saudi Arabia, India, Egypt, Australia and China were among the top five recipients of arms. The largest buyers of Swiss-made weapons during this period were Australia, followed by China and Denmark.

In 2020, the main buyer of Swiss war material was Denmark, with deliveries worth 160 million Swiss francs (147 million euros). This was followed by Germany and Indonesia with 111 million francs (102 million euros) each. In fourth place was Botswana with just under 85 million francs (78 million euros), followed by Romania with 59 million francs (54 million euros). Denmark, Botswana and Romania received armored wheeled vehicles, Indonesia air defense systems. This is shown by the statistics published by the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (Seco) published statistics (see below).

A comparison of the continents shows the following trend: Swiss companies sold the majority of all war material (62%) to European countries. 14% of all exported goods went to Asia. Exports to Africa amounted to almost ten percent, an increase of a full eight percent compared to the previous year. In total, Swiss companies exported to 62 countries last year. Not every recipient country uses the weapons itself. According to Seco, some of the weapons are processed and passed on. In the case of the delivery of war material, the recipient must sign the so-called “non-re-export declaration” (end-use certificate, EUC). In this he undertakes not to re-export the material. Swiss armored vehicles and ammunition particularly in demand

At 38%, armored vehicles accounted for the largest share of all goods exported from Switzerland. Ammunition and ammunition components accounted for 23 percent, followed by fire control equipment with just under 17 percent. Weapons of all calibers accounted for twelve percent, and fighter aircraft components for four percent. The largest ammunition manufacturer in Switzerland is RUAG Ammotec, based in Thun in the Bernese Oberland. Ammotec is part of the state-owned defense and technology company RUAG. Specifically, Ammotec manufactures small caliber ammunition and offensive, defensive and training hand grenades for civilian and military purposes. Its history goes back to the Steffisburg powder mill built in 1586. Last week it was announced that Ammotec does not have to remain in the possession of the state and may be sold. Preference is to be given to a local buyer if possible and the production site in Thun is to be retained. In addition to Switzerland, Ammotec also has sites in Austria, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and the USA. Two years ago, RUAG Ammotec Austria signed a partnership agreement with the Austrian Armed Forces. Which Swiss companies export war material was a secret for a long time. In its annual statistics, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (Seco) only disclosed the category of exported goods and the destination countries. After a five-year legal dispute with the Swiss “WOZ. Die Wochenzeitung” and a legal ruling by the Swiss Federal Supreme Court, Seco has now also had to disclose the names of the arms producers, including the export amount and the type of arms sold, since last year. Many questions remain unanswered

The extent to which stricter export rules will prevent Swiss weapons from ending up in conflict zones and being used against the civilian population remains an open question. Exports are already subject to compliance with international law and international obligations. Globalized trade makes it possible for Swiss-made weapons to be used in armed conflicts after all. The question of so-called “dual-use goods” also arises.

These are goods that can be used for both civilian and military purposes, such as chemicals and machine tools. Together with special military goods (e.g. military training aircraft, military simulators) that are not directly designed for combat purposes, they are not subject to the Swiss War Material Act, but to federal goods control legislation. The export of both categories of goods can only be refused if the recipient state is on an international embargo list or if “there is reason to believe that the export will support a terrorist group or organized crime”. The question of the provisions on the delivery of spare parts that Swiss companies have agreed with the respective buyer states when concluding the contract also remains open.