Russia’s defense industry does not have it easy. On the one hand, the industry is hungry for potential customers in the West with its technically competitive products, but on the other hand, political and economic conditions are preventing potential contracts from being concluded.

The Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), with which Washington sanctions or threatens with sanctions allied, friendly or US-equipped states that want to procure Russian major weapons systems, is proving to be a decisive stumbling block. Turkey, for example, recently found out that these threats are not just empty words, as it has been sanctioned because of the Turkey, which is not receiving modern F-35 fighter jets due to the procurement of Russian S-400 air defense systems. In addition, the EU sanctions and restrictions against Moscow also include so-called dual-use goods, which further restricts the availability of high-tech products in Russia.

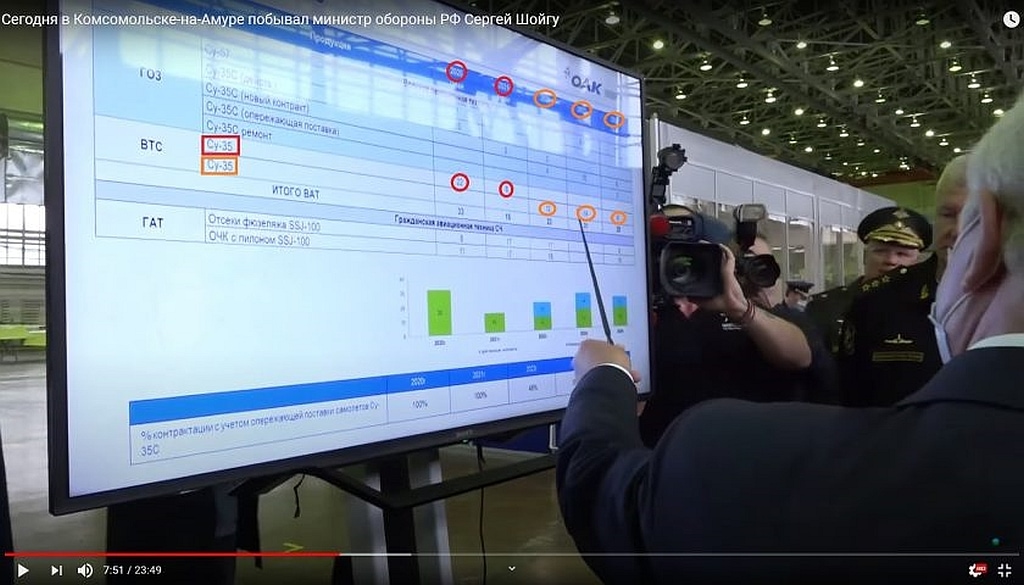

Su-35 primarily affected

This has recently had an impact on the Su-35 in particular: although there is no direct evidence that European components or components manufactured in Taiwan or South Korea in accordance with US patents were installed in the Su-35, as Russia does not have a competitive semiconductor industry and therefore no domestic alternatives for certain chip classes such as high-performance DSPs and FPGAs (further information in this and in this article), this cannot be ruled out either. The Su-35, which entered service with the Russian Air Force in February 2014, was in any case the fourth derivative of the Su-27 design and was the first representative of a new generation of fighter jets, generally referred to in specialist circles as Generation 4++. The (Russian) philosophy behind it was based primarily on the extreme “super maneuverability” and versatility of the Su-27 airframe, as Sukhoi test pilot Sergei Bogdan explained to Militär Aktuell. Western pilots, however, consider this to be outdated or pointless due to BVR and sensors. Nevertheless, the thrust vector technologies developed for the Su-35 are also being used – in a refined form – for the next (fifth) generation Su-57. They were also sold to China, the only export customer to date, as part of a technology transfer agreement that accompanied the contract for the purchase of Su-35 fighters. In the meantime, the technology has also been used in China’s J-10C single-jet fighter. However, the export to Beijing was primarily about the Su-35 engines. The 117S from NPO-Saturn represent a comprehensive further development based on the AL-31F. The focus was on increasing the dry thrust in order to achieve supersonic speeds without afterburner (supercruise). To achieve this, the fan diameter was increased by three percent (932 instead of 905 millimetres) and a completely revised digital control system (FADEC) was installed. At the same time, the thrust vector control of the AL-31FP was adopted. The intervals between overhauls (a weak point of previous and current Chinese turbofan engines) were increased from 500 to 1,000 hours and the maximum service life from 1,500 to 4,000 hours.

The 117S also bears the designation AL-41FA1 (not to be confused with the AL-41F) and was developed as an interim solution for the Su-57 until its originally planned engine, designated Product-30 (Russian: Изделие-30), is ready for series production. Russia had previously asked China to buy more Su-35 fighter jets (than the 24) in exchange for more AL-31Fs. These engines in turn powered the first J-20 stealth fighters. Until the WS-10C and WS-15 go into series production, Beijing will have to continue to rely on them, while the Su-35’s radar, navigation system and other electronic components are inferior to Chinese systems, such as those installed in the J-16.

According to various defense media, Egypt, the next export customer, has now had to cancel its order for 24 Su-35SE (-E always stands for an export version), which was ordered in 2019 for just under two billion euros. This is despite the fact that between 15 and 17 of the Flanker-Es destined for Cairo have already been produced and are already in service in Irkutsk (tactical numbers 9211 and 9212) have already been photographed in flight. The aircraft are now – as can be seen on satellite images from 2021 – at the Sukhoi production plant KNAAz in Komsomolsk on the Amur and are unlikely to be delivered to al-Quwwat al-Jawwiya Il Misriya (EAF, Egyptian Air Force). After all, some aircraft had been temporarily tested by the Egyptians, but the tests were probably rather sobering. During tests against the brand new Rafále fighter jets of the Egyptian Air Force the two or three acquired Su-35s with their Irbis-E PESA (passive electronically scanned array) radars came out on top. clearly got the short end of the stick and were (simulated) shot down as a result.

The experience apparently evoked painful memories in Cairo, because years ago the Russians had already promised to convert those from Zhuk-ME to AESA radar (today’s international standard with active beam steering, sometimes even with a swiveling antenna) when procuring a total of 50 MiG-29M2s and MiG-35s (the order volume at the time was just under two billion euros). But then nothing happened for years. As a consequence, Cairo ordered “in the usual over-optimism and completely pointless and unrealistic” (according to the successful military aviation author Tom Cooper) the Su-35 fighter jets. Sounds illogical, and it is, although with this step and the associated R-77 weapon options, Cairo probably also wanted to free itself from what it perceived to be the US’s “strangulation” of not being able to order F-15s or modern BVR missiles (radar-guided, over-the-horizon) such as AIM-120Cs due to concerns on the part of Israel. And this despite the fact that Qatar, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Jordan, Oman and Turkey already have such systems.

In addition, the Su-35s are still equipped with the PESA radar and the EAF would have to wait for years (and pay a lot) until the Russians have developed a suitable AESA radar. And that – contrary to glossy brochures and flyers at trade fairs – is apparently still dependent on critical foreign dual-use high-tech components such as semiconductors from Taiwan, South Korea or Israel. It is precisely these components that are now failing to materialize in times of a global semiconductor shortage. According to insiders, Russia has asked its potential partners for patience and further deadline extensions “in order to solve the technical problems that have arisen”. Against this backdrop, Cairo is likely to have been persuaded not to procure a technically inferior device that could hardly be integrated, which will also be confronted with years of restrictions and capability losses due to CAATSA measures. After all, with the exception of Rafále, MiG-29M2 and Ka-52 (the latter were ordered before CAATSA came into force), all of Egypt’s air equipment has been procured from the USA since the breakaway from the USSR in 1973. This includes more than 200 F-16A-D jets, the mainstay of the Egyptian Air Force. Following the “carrot and stick” model, the US Department of Defense only awarded a contract to Lockheed Martin to upgrade Egypt’s AH-64D Apache Longbow attack helicopters to the latest standard AH-64E Apache Guardian.

And now to Tehran?

Another long-time acquaintance of the author is the Iranian military aviation journalist and publicist Babak Taghvaei. Because of his reporting on the Iranian Air Force (IRIAF) and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (IRCG-AF) and his corresponding photos, he was advised to leave his homeland and now lives in Cyprus. Babak recently reported – as did the Iranian news agency MEHR – that Iran and Russia would sign a 20-year defense agreement worth almost ten billion euros this month. As part of this agreement, Moscow would allegedly upgrade the Islamic Republic of Iran’s air force with the very 24 Sukhoi Su-35SEs that Egypt is currently without. Two S-400 anti-aircraft missile systems and a military satellite would also be added. It remains to be seen whether the deal will go through, but insiders say it is not unlikely. On the one hand, this is supported by the fact that the UN arms embargo under UN Resolution 2231 expired in October 2020 following the 2015 JCPOA nuclear agreement – which has now been renegotiated in Vienna following the US withdrawal – and was not extended in the face of US opposition. On the other hand, Tehran is still hardly allowed to export any oil and therefore does not actually have the funds required for such a deal from an economic perspective. According to the sources mentioned, however, the Russian deal is to be based on Iranian oil for Moscow, which Russia can then sell. In view of internal rivalries, however, it remains to be seen whether the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC, more than twice the budget of the regular armed forces), which effectively controls the mullah state, would allow the IRIAF the status of operating such a powerful weapon compared to the other severely outdated air inventory of pre-1979 US models and later Russian and Chinese purchases. Babak says that Iranian and Russian defense officials had already negotiated the acquisition of the 24 Egyptian aircraft during a visit by Major General and Chief of General Staff Mohammad Bagheri on October 17, 2021. This would also fit with the draft budget law proposed by the new government of Ebrahim Raisi to strengthen the air force capacity for 1401, which was submitted to the Islamic Consultative Assembly on December 12, 1400 (Islamic calendar, since the flight of Muhammad to Medina). According to other (as yet unverified) sources, 32 Iranian pilots are already undergoing Su-35 training in Krasnodar.

Once before, after the end of the UN arms embargo, Iran began negotiations with Russian officials on the purchase of 12 to 18 Yak-130 trainers and 18 to 24 Su-30SM (two-seat multi-role combat aircraft). One of Iran’s most important demands at the time was the possibility of assembling the aircraft at Iranian aircraft factories (HESA) and the possibility of manufacturing their parts locally. At the time, this was rejected by Russia. In addition to Egypt, Indonesia is also interested in the Russian model, as its air force plans and initial plans to take over the domestic Eurofighter fleet also caused discussion in this country. Back in February 2018, Russia and Indonesia signed a contract for eleven Su-35s worth one billion euros. According to the then US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, this led to the threat of US sanctions due to CAATSA, which was openly communicated. Indonesian Air Chief Fadgar Prasteyo told local media in Jakarta: “Yes, regarding the Su-35, unfortunately we had to abandon our plans with a teary eye. We can no longer talk about it.” In December 2021, Indonesia then officially confirmed that it had abandoned this acquisition and would now French Dassault Rafále instead and possibly also American F-15EXs are to be purchased instead. In addition, it is still involved in the 5th generation KF-XX (KF-21) project with South Korea, even if the share financing is unsatisfactory from Seoul’s point of view.

Nor did Russia find a customer in Algeria, which for a long time was an important buyer of Russian jets and other military hardware (but also returned the first twelve of the 28 MiG-29SMTs originally planned in 2008 due to old and faulty components being installed and subsequently received Su-30MKAs) and, ex-equo with Egypt, has the strongest air force on the African continent. Algiers also decided against buying the Su-35 because it was also dissatisfied with the fact that the aircraft still has a PESA and not an AESA radar. Russia had previously announced that it had signed agreements with Algeria for the delivery of the Su-35. The al-Quwwat al-Jawwiya al-Jaza’eriya (Algerian Air Force) decided instead to upgrade its existing fleet of Su-30MKAs, which had already been supplied by Russia from 2007. Myanmar (formerly Burma), which is largely isolated worldwide, ordered six two-seater Su-30SM2s in January 2018 for just under 200 million euros; at least two aircraft are apparently likely to have been delivered in February 2021 – despite the internationally outlawed re-installation of the military junta (Tatmadaw) – and have already been used against rebels of the Kachin Independence Army in live firing (throwing). However, Russian industry recently had to request additional deadlines for the completion of the remaining four aircraft. The alleged reason for this was problems with composite materials.