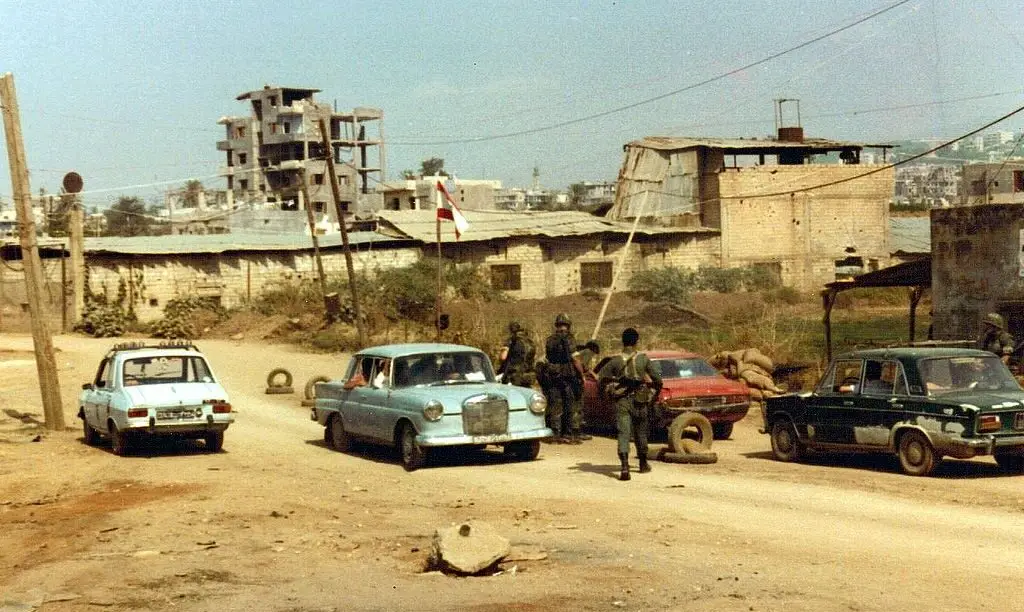

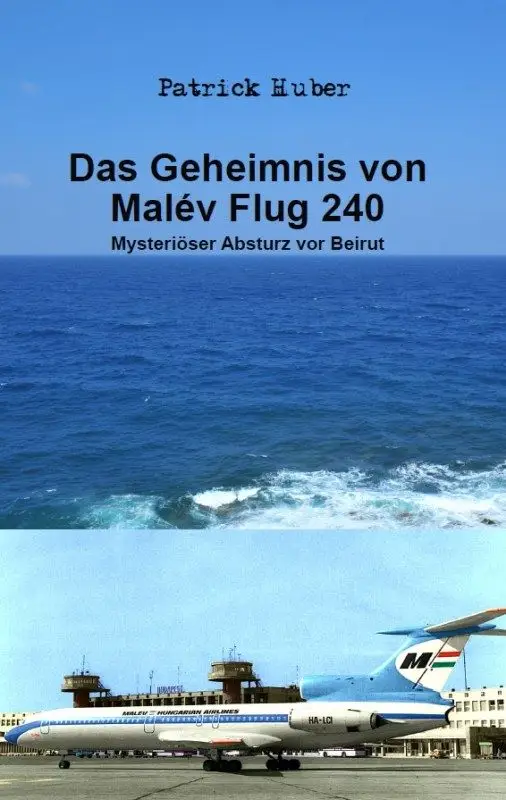

Lebanon, once a prosperous state, known as the “Switzerland of the Middle East” in the 1950s and 1960s, has been sinking into chaos, violence and terror for many decades. A bloody civil war raged in Lebanon from 1975 to 1990. And since the end of this civil war, the terrorist militia Hezbollah, founded in 1982, has been gaining more and more influence. The Islamists currently control large parts of the south of the country as well as districts in the capital Beirut, which is why Israel has been conducting a military operation on the ground and in the air for several weeks to combat Hezbollah, which is financed by Iran. Today, Lebanon is de facto a “failed state” in which the government and state executive powers only have very limited influence. State structures have largely eroded. Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that an equally mysterious and dramatic event that took place almost 50 years ago has been forgotten: the disappearance of a plane from the Hungarian Malév on September 30, 1975 shortly before landing in Beirut. There is reliable evidence that the Tupolev Tu-154 was shot down by a fighter jet because members of the Palestinian terrorist organization PLO (Palestine Liberal Organization) were suspected of being on board. This is the story of Malév Flight 240, about which I have also written the only German-language book to date. For my research, I traveled to Budapest and conducted exclusive interviews with several contemporary witnesses. My book “The Mystery of Malév Flight 240: Mysterious Crash off Beirut” is available from the publisher’s online store and from any bookshop, quoting the ISBN.

Highly qualified crew

The crew was extremely experienced. It consisted of commander János Pintér, co-pilot Károly Kvasz, flight engineer István Horváth, pilot/navigator Árpád Mohovits and an additional technician named László Majoros. The commander (42 years old) had around 3,700 hours of flying experience and was even qualified as an instructor for the Tu-154. The first officer (36) could look back on around 3,300 hours of experience. The flight engineer and the additional pilot were not beginners either. The cabin crew on duty that day were purser Richárd Fried (35) and stewardesses Ágnes Kmeth (39), Mercedesz Szentpály (25), Miklósné Herczeg (25) and Lászlóné Németh (24). Németh, the youngest of the entire crew, had only been a stewardess at Malév for just under two weeks. It was one of her first international flights.

International audience on board the Tu-154

The aircraft with the registration HA-LCI was just over two years old and technically in perfect condition. Produced and delivered as the basic model Tu-154 with the serial number (c/n) 74A053, the aircraft had previously flown with the Soviet Aeroflot (as CCCP-85053) and the Egyptian Egypt Air (as SU-AXG) before it was modernized and converted to the Tu-154A. Malév then received the aircraft as HA-LCI and christened it with the Hungarian name “Ilona”, which translates as “the radiant one”. It was not until June 20, 1975, around three months before the accident flight, that the Hungarian flag carrier put the jet into service. By September 29, 1975, the “Ilona” had just under 1,200 hours in its logbook. https://militaeraktuell.at/5-sichten-auf-die-welt-012/ On that Monday, 50 passengers checked in for flight MA240 at Terminal 1 of Ferihegy Airport (IATA code: BUD, ICAO code: LHBP) in Budapest, which was built in 1950. A total of 37 travelers came from Lebanon and Egypt according to their citizenship. Some of these Arabs were Palestinians who had undergone military training in Hungary. At the behest of the Soviet Union, Hungary supported the PLO. Also booked in were some nuns, a British-Egyptian couple with their three-year-old daughter and two Finns – a UN diplomat and a UN military observer. Apart from the crew, there was only one other Hungarian on board: Gábor Glausius. He was a father of two who was on an unspecified business trip to Baghdad and wanted to travel there via Beirut. According to the Hungarian Ministry of Transport, Glausius was the head of the Hungarian government’s foreign trade department. At the age of almost 30, he had already received the award for “services to the socialist fatherland”, which brought with it many privileges and (travel) freedoms. Under the Kádár regime (“Those who are not against us are with us!”) in Hungary in the 1970s, such an order was usually only awarded to particularly strict and loyal communists.

High-ranking PLO officials on the passenger list

A high-ranking delegation from the Palestinian terrorist organization PLO was booked on the flight, and this circumstance is most likely the explanation for the shooting down of flight MA240, which was considered a certainty by experts. One day earlier, on September 28, this group had opened a kind of “embassy”, a so-called liaison office, in Budapest and was more or less openly supported by the Soviet Union and, on its instructions, by other socialist and communist states. Hungary was decidedly anti-Israeli at the time and promoted the Palestinian agitation of the terrorist Yasser Arafat. terrorist Yasser Arafatwho had been PLO chairman since 1969. 53 members of the PLO leadership, probably including Khaled al-Fahoum, who had founded the PLO together with Yassir Arafat and had been president of the “Palestinian parliament in exile” since 1971, were booked on flight 240 and a special VIP check-in was available for these men at Budapest airport that day – but the PLO members never showed up for check-in, instead traveling on later by train from Budapest to Belgrade. Such last-minute changes to the PLO leadership’s travel plans were quite common at the time, for fear of attacks by the secret services, as I was able to find out during my research for the book.

“We don’t know who did it, but it’s clear that Palestinians booked on the flight were the target.”

Erkki Tuomioja, früherer finnischer Außenminister

Illegal military cargo

It is also known that a group of Finnish soldiers wanted to book tickets for exactly this flight as early as mid-September, but were told by the Malév sales office that MA240 was already “fully booked”. This statement seems very strange, as even with the PLO delegation just over 100 passengers were booked and therefore a good 50 to 60 seats were free in the cabin of the Tu-154A. The fact that Malév nevertheless did not want to sell any more seats was most probably due to the fact that the capacity was needed for additional cargo. On September 29, crates with an unknown cargo were loaded into the fuselage of the Tupolev with the registration HA-LCI. Hungarian sources speak of “four tons” – a figure that cannot be independently verified, however. Although there is still no official confirmation of this, it is very likely that the weapons of war were illegally transported on board the civilian aircraft and were destined for one (or more) of the civil war parties in Lebanon, but presumably for the Hungarian-backed PLO. This is also supported by the fact that, according to informants from Hungary, the plane was parked in a particularly remote position at the airport for boarding that evening. For a period of around 15 minutes, the apron lighting was even switched off in the vicinity of the HA-LCI – an absolutely unusual procedure. The authorities later spoke of a “power failure” and denied that the lights had been switched off as planned.

Start hours late

Flight MA240 was supposed to take off from Budapest at 16:50 local time (14:50 UTC), but the take-off was repeatedly postponed. The airline did not give an official reason for this, even later. Passengers even had to leave the Tupolev twice.

In the early hours of September 30, at around 00:19 UTC (03:19 Beirut local time), the pilots of flight MA 240 reported to the air traffic controller in Nicosia (Cyprus). This radio communication was inconspicuous and only contained standard information such as flight altitude and position reports. At this point, the HA-LCI was flying at flight level 370 (37,000 feet, approximately 11,300 meters). Shortly afterwards, the controller cleared the Tupolev for descent: “Malév 240 you are cleared to descend to flight level 110.” A short time later, air traffic control in Nicosia instructed the crew of flight 240 to contact Beirut on the frequency 119.3 MHz, which they did at 00:33 UTC. The controller in Beirut cleared the Malév to an altitude of 6,000 feet (about 1,800 meters). However, the Beirut controller could not see the Hungarian aircraft on his radar. This was because the system had been defective for some time as a result of the civil war turmoil. The airport’s instrument landing system, or ILS for short, was also out of order. Commander Pintér and his first officer Kvasz therefore had to carry out a visual approach. But such a maneuver was certainly no problem for the experienced crew, especially as the weather conditions that night were ideal for it. Visibility was more than 20 kilometers, the wind was light, Beirut’s runway lighting was activated and the illuminated skyline of the city showed the crew the way to the airport, which is located directly on the coast.

In the early hours of September 30, at around 00:19 UTC (03:19 Beirut local time), the pilots of flight MA 240 reported to the air traffic controller in Nicosia (Cyprus). This radio communication was inconspicuous and only contained standard information such as flight altitude and position reports. At this point, the HA-LCI was flying at flight level 370 (37,000 feet, approximately 11,300 meters). Shortly afterwards, the controller cleared the Tupolev for descent: “Malév 240 you are cleared to descend to flight level 110.” A short time later, air traffic control in Nicosia instructed the crew of flight 240 to contact Beirut on the frequency 119.3 MHz, which they did at 00:33 UTC. The controller in Beirut cleared the Malév to an altitude of 6,000 feet (about 1,800 meters). However, the Beirut controller could not see the Hungarian aircraft on his radar. This was because the system had been defective for some time as a result of the civil war turmoil. The airport’s instrument landing system, or ILS for short, was also out of order. Commander Pintér and his first officer Kvasz therefore had to carry out a visual approach. But such a maneuver was certainly no problem for the experienced crew, especially as the weather conditions that night were ideal for it. Visibility was more than 20 kilometers, the wind was light, Beirut’s runway lighting was activated and the illuminated skyline of the city showed the crew the way to the airport, which is located directly on the coast.

Major cover-up operation

After the Lebanese air traffic controller could no longer reach the aircraft from Hungary by radio, he initially phoned other air traffic control units and asked whether the Tupolev had possibly landed in Cyprus, Syria or Turkey. However, all his inquiries in this regard were answered in the negative. The suspicions that MA240 had crashed became more and more substantiated. Later, the pilot on duty that night was to testify that there were no signs of any problems during the last radio contact with MA240. Everything had been completely normal. https://militaeraktuell.at/wehrpolitischer-dachverband-bundesheer/ During a large-scale search operation involving ships from Lebanon and a Royal Air Force C-130 Hercules, debris and individual bodies were eventually discovered. But instead of carrying out a recovery of bodies and wreckage, as would be customary internationally, Hungary spread a cloak of silence over the crash of its Tupolev. Neither the wreckage nor the flight recorder were ever recovered, although this would have been technically possible – and still is today. Hungary even denied that bodies had been found, although Arab media reported on the recovery of victims and their burial – including photos. A passenger list or a transcript of the radio traffic were also never published, and an official investigation report – neither from Lebanon nor from Hungary – does not exist 49 years after the crash.

One shooting is considered certain

Although the cause of the crash cannot be clarified beyond doubt, there is strong evidence that the plane was shot down by an air-to-air missile, including the testimony of a British soldier who was stationed at the RAF station in Cyprus at the time. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, several Malév employees also declared “off the record” that Flight 240 had been “destroyed by an external force”, i.e. had been shot down. The former chief pilot András Fülöp was the most outspoken: “The plane was hit by two missiles fired by a fighter jet. The air traffic controller told me this, but added that he had only told me this on a personal basis. If he is officially questioned about it, he will deny it. He has a family and doesn’t want to get into a situation where he gets into trouble. That was it. And that’s what I told our director.”

“Secret” document and “hush money” for surviving relatives of Hungarian victims

In 2003, almost 30 years after the disaster, the Democratic politician Miklós Csapody brought the issue back into the public eye in Hungary and wanted to know from the government whether, after almost three decades, a comprehensive investigation into the case and the recovery of the victims could finally be expected. In the same year, the “Hungarian National Security Service” (Nemzetbiztonsági Hivatal, NBH for short) produced two reports of its own on the crash of flight MA240. These reports stated, among other things, that the original documents relating to the accident could unfortunately no longer be found. A year later, the Hungarian government set up a fund endowed with 100 million forints for the search and recovery of the wreckage, but again took no further steps in this direction. When the 2003 NBH reports were again made public in 2007, the minister responsible for overseeing the security service declared that these two documents had been classified as “secret”. In 2009, the then Hungarian government finally contacted a professional international underwater salvage company and had a quote prepared for the search and recovery of the remains of flight MA240. However, after the salvage company’s offer was submitted, the Hungarian government again did nothing. https://militaeraktuell.at/prototyp-europaeisches-aesa-radar-ecrs-mk2-luft/ Instead, the money budgeted for the search and salvage of the wreckage was used to compensate the Hungarian survivors. The victims received 4,000,000 forints (the equivalent of around 14,800 euros at the time) per person and, according to Lászlo Németh, had to sign a declaration in which they undertook not to make any more inquiries about the case and not to comment on it publicly. By his own account, Németh was the only one of the Hungarian relatives who did not accept the money and refused to sign this questionable agreement.

Relatives continue to hope for clarification

In this form, the events surrounding Hungary’s obvious obstruction of the investigation into the mysterious Malév 240 crash can and must be described as unique in the history of modern commercial aviation. I am not aware of a single other crash of this magnitude that has been investigated so superficially, not to say almost not at all. At the end of the day, it could simply be about money. Because if the remains of flight MA240 are recovered and it turns out that the jet was actually carrying illegal military goods on its already irresponsible high-risk flight to a civil war zone and was shot down by a fighter jet of a party involved in the conflict, this could still cause a major international diplomatic uproar today in view of the many foreign victims – and at the same time result in claims for millions in damages against Hungary from the surviving dependants of the 60 passengers. After all, Malév, which slipped into insolvency in 2012, was a state-owned airline at the time of the accident, which would make Hungary directly liable. It is even possible that the insurance company would try to reclaim the money paid out for the crashed Tupolev Tu-154A. In addition, it might even be possible to prove which weapon system or caliber (Soviet or Western) was used to bring down Flight 240 based on the bullet damage to the wreckage of the Tu-154A.  And so it is hardly surprising that even people who are far from being conspiracy theorists sometimes have the feeling that – at least from the point of view of some Hungarian politicians – there may well be some weighty reasons to keep the wreck of the ill-fated HA-LCI resting in its wet grave on the seabed off Lebanon, so that it can never reveal its potentially highly explosive secrets to the Hungarian public. The current military conflict in Lebanon, from where Hezbollah fires rockets at Israel on a daily basis and Israel’s air force strikes back, is another factor that is unlikely to make salvaging the wreck any more likely. But as we all know, hope dies last for the surviving relatives, who will be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the tragedy next year.

And so it is hardly surprising that even people who are far from being conspiracy theorists sometimes have the feeling that – at least from the point of view of some Hungarian politicians – there may well be some weighty reasons to keep the wreck of the ill-fated HA-LCI resting in its wet grave on the seabed off Lebanon, so that it can never reveal its potentially highly explosive secrets to the Hungarian public. The current military conflict in Lebanon, from where Hezbollah fires rockets at Israel on a daily basis and Israel’s air force strikes back, is another factor that is unlikely to make salvaging the wreck any more likely. But as we all know, hope dies last for the surviving relatives, who will be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the tragedy next year.