The Institute for Peacekeeping and Conflict Management (IFK), together with the Directorate for Security Policy, recently published the the latest edition of the Annual Security Policy Preview was published. Together with IFK Director Major General Johann Frank, we analyzed the risks for Austria and took a look into the future.

Major General, what is the state of Austrian security in 2021?

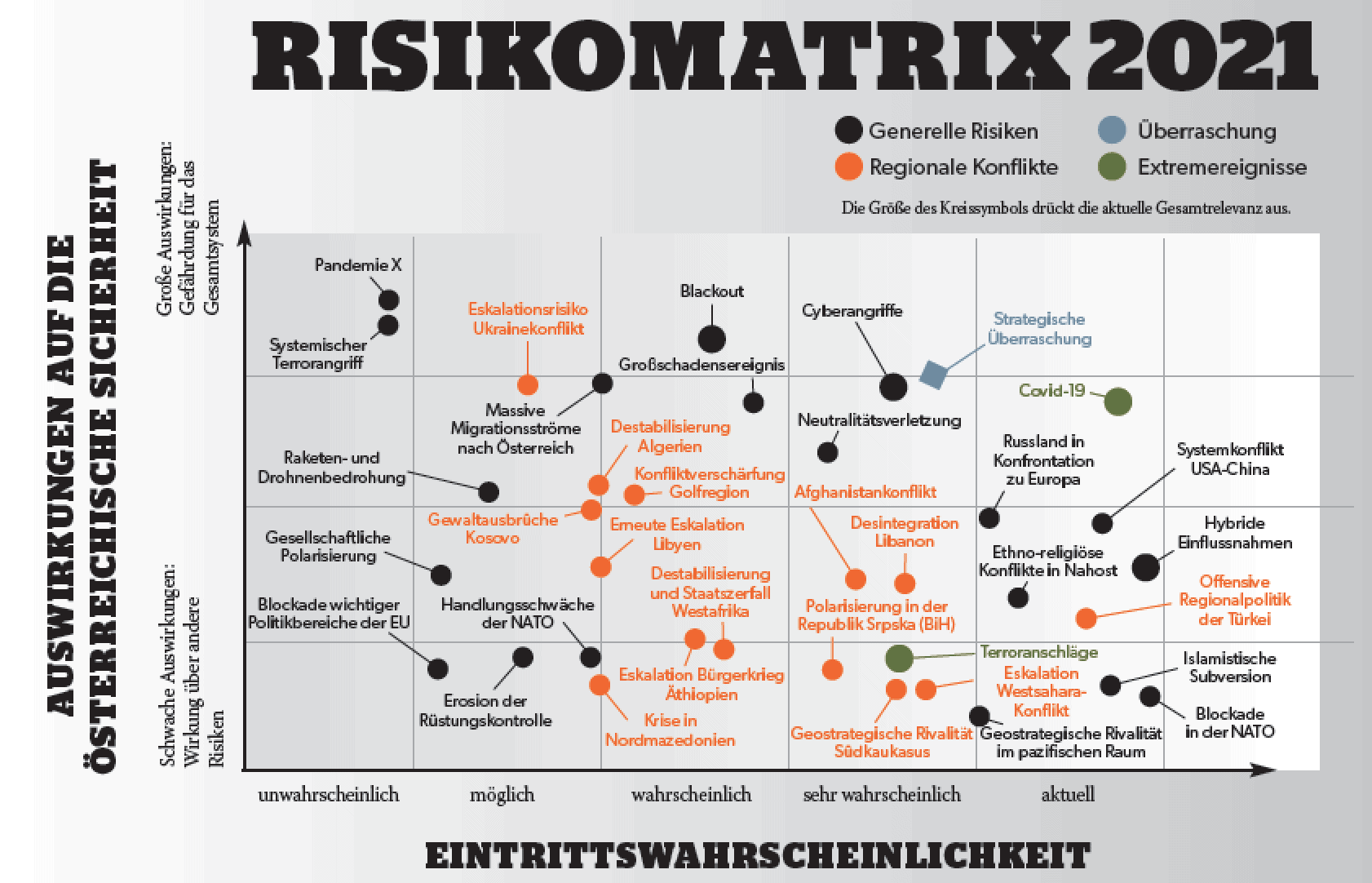

Our security is under more pressure than it has been for a long time! The strategic impact of the coronavirus pandemic is a dominant factor in the current risk picture. The main focus is still on getting the direct medical effects under control. However, coronavirus also has a wide range of security policy implications, giving existing conflicts a new dynamic, allowing new conflicts to arise and continuing geopolitical power shifts. In a way, the pandemic is acting as a catalyst for trends and developments, some of which were already noticeable but often not yet visible. The bottom line is that the security situation in Austria has definitely not improved.

That was also the basic tenor of previous editions of the Annual Security Policy Preview, wasn’t it?

That was also the basic tenor of previous editions of the Annual Security Policy Preview, wasn’t it?

Yes, but there is now a serious difference: some of the risks that were previously analyzed in a rather abstract and generic way have actually occurred in the meantime.

You’re talking about the pandemic and the terrorist attack in Vienna?

Exactly. There have also been massive cyber attacks on the Foreign Ministry, for example. In addition, Austria is increasingly exposed to hybrid influence operations – albeit at a low level – which have become visible through the espionage cases, disinformation campaigns surrounding corona or the Austrian blockade within the framework of the NATO Partnership for Peace. Contrary to what is often portrayed, Austria is not an island of the blessed; Austrian security policy is facing a test case in the face of these diverse challenges.

“Corona also has a variety of security policy implications: existing conflicts are gaining new momentum, new conflicts may arise and geopolitical power shifts are continuing.”

What other risks should we definitely have on our radar?

Of course, extreme events that threaten resilience, such as major incidents and blackouts, could only be avoided in mid-January with considerable effort. In addition to the national level, our analyses also take into account the global and regional levels. These levels interact with each other and international crises are increasingly having an impact on Austria under the current framework conditions. This is new to this extent and distinguishes the current security situation from the past. Let‘ s start with the global level.

The main focus here is on the systemic conflict between the USA and China. Regardless of who is at the head of the US administration, this will continue to intensify, particularly in the areas of financial and economic policy. This also includes a selective escalation of a maritime nature in the Pacific region, for example. For Europe, this raises the question of which side it will take. Depending on the decision, a negative hybrid influence from the other side can be expected. We are talking about economic measures and sanctions, but also the closing of market and technology access.

Could Europe avoid this risk by adopting a neutral role? Or is there only the motto “for us or against us”?

This will be the key question, whereby Europe is certainly not neutral due to its value base, but is clearly in the camp of the West. However, from Brussels’ point of view, China is not just a rival, but also a partner that opens up economic opportunities. In my view, Europe should therefore take its own side in this dispute. Of course, this would require an increase in strategic autonomy and its own economic and military capacity to act. Let’s move on to the regional level.

Following the withdrawal of the former superpower USA, which the new President Joe Biden will not change significantly, the wing powers Russia and Turkey as well as players from the Gulf region are gaining room for maneuver, which they are actively exploiting. This is one of the reasons why Europe is now surrounded by a belt of crises that stretches from West Africa to the Middle East and the Caucasus region. The only stable thing in this neighborhood is instability and, in view of the efforts of the aforementioned actors, further crises and conflicts are likely to break out there, while existing conflicts will not be resolved.

So the already uncertain environment is becoming even more uncertain?

This is certainly to be expected. Countries that are already in crisis are likely to come under even more pressure due to the economic impact of the coronavirus crisis and in many places, state structures are unlikely to be able to provide sufficient basic services for the population. This will then provide a breeding ground for all forms of extremism, including radicalization and terrorism. The danger is that this will also affect previously stable anchor states in the region – such as Algeria, Egypt and Jordan.

Could Moscow, Ankara and the Gulf states not also have a stabilizing effect on the region in the long term? After all, no country should have an interest in wars, conflicts and instability right on its doorstep.

There will definitely be a new regulatory framework. The only question is whether this framework can be reconciled with European values and legal concepts. Up to now, these have aimed to ensure that all countries in the world have the most democratic and liberal forms of government possible.

From a European perspective, is it perhaps necessary to abandon this selfish goal?

If you compare the European Security Strategy of 2003 with that of 2016, then you have already done so to some extent. In 2003, Europe was surrounded by a ring of friends and all its neighbors wanted to adopt the European model of society or join the EU of their own free will. Today, we are talking about a ring of fire and authoritarian state systems are gaining in importance – so the basic conditions have completely changed.

Let’s return to the risk matrix: If you compare the 2021 picture with that of 2020, many parallels can be seen. How long will it take for this kind of risk picture changes dramatically?

We would have done a poor job if the matrix looked completely different every year. Topics such as terrorism, pandemics and blackouts have featured prominently for years and will continue to do so. However, there are also risks that are new to the matrix or have shifted in importance. For example, we now have the US-China system conflict more prominently on the agenda because it also plays a role in areas that are important for Europe – from 5G expansion to access to economic areas and climate change. A new area of concern for us is the social fragmentation processes in Western societies, which undermine the population’s trust in state institutions.

Are there risks in the matrix that would result in a national defense case?

No, not for the next twelve to 18 months. These risks would be shown in red and, as they would have the greatest impact on our country and our society, they must be avoided at all costs through appropriate security precautions and preventive measures. In this respect, our risk analysis could also be seen as a matrix of opportunities that shows possibilities that can be taken at an early stage to prevent negative developments from occurring in the first place. This also means that, as a consequence of the coronavirus pandemic, we will have to think a little differently about security policy in the future.

“Many risks can influence each other, which can have far-reaching cascading effects.”

In what way?

In the past, we have focused almost exclusively on probabilities of occurrence and prioritized risks accordingly. However, the pandemic has shown us that we need to pay more attention to the potential intensity of damage. In our analyses, we also see that, as in the recent Nagorno-Karabakh war, conflicts are very likely to be fought by military means again and that military successes on the battlefield can be converted into political capital. This was considered practically impossible in recent years, but could now also have a precedent effect on other conflicts. To what extent must the individual risks presented be seen in their entirety and as interdependent, and not just viewed individually?

This is the most important aspect and precisely what makes the analysis so difficult. Many risks are interdependent, which can have far-reaching cascading effects. From a conflict analysis perspective, the outbreak of the First World War, for example, can certainly be seen as a build-up of many smaller, actually regionally limited risks. Many American analysts see the danger of war between the USA and China in a very similar way. They practically rule out a war based on strategic considerations. However, it is possible that a local misunderstanding or the misconduct of an ally could trigger a domino effect that would then be unstoppable and would of course also have a huge impact on Europe and Austria.

Here the Annual Security Policy Forecast 2021 is available for free download.