Space, militarization, international law: The leading German space law expert Stephan Hobe on space, which is gradually developing into the next conflict-laden arena of geopolitics.

For decades, space seemed to be the symbol of human progress: peaceful cooperation, scientific vision, technological masterpieces. However, the supposed paradise above the clouds has long since been tipped over. Communication networks, reconnaissance, navigation; hardly any military operation today can do without orbital support. States are arming themselves, private players are getting involved and international law is reaching its limits. This is why Stephan Hobe, Director of the Institute for Air, Space and Cyber Law at the University of Cologne, warns in an interview with Militär Aktuell: “Space is becoming the Theater of War. And international law stands by with a blunt sword.” An interview as part of the 2nd Space Symposium of IABG and IDLw in Ottobrunn near Munich.

Professor Hobe, your Institute for Air, Space and Cyber Law has just celebrated its 100th anniversary. Was law really already in the sky so early on?

The aviation law yes. The institute was founded as early as 1925, at that time still exclusively for aviation. The first international agreement, the Warsaw Convention of 1929, is still in force today. With the emergence of space travel in the 1950s, space law was added and, in the last ten years, cyber law. Today, these areas overlap massively.

“Space is becoming the Theater of War. And international law stands by with a blunt sword.”

How did you personally come to deal with space law of all things?

Coincidence. I originally wanted to do a doctorate in maritime law until my supervisor said: “Why don’t you do something new: space.” I was completely amazed that there were any legal regulations at all. So I started in Kiel in 1984, later in Montreal, and have stuck with it ever since.

Was space travel intended to be military from the outset?

Yes, the romantic narrative of mankind’s pioneering spirit is historical cosmetics. In fact, space travel was an armaments project from the very beginning. The USA and the Soviet Union needed space to maintain their respective Cold War deterrence scenarios. One key figure was Werner von Braun. A German rocket engineer who had worked on the Second World War played a key role in the development of the V2 rocket for the Nazi regime and went to the USA after the end of the war. There he became the leading head of the American space program at NASA and the architect of the Apollo moon mission. In any case, the Americans had no qualms about accepting someone like Braun, who had worked for the National Socialists, into their ranks.

When did space infrastructure really become militarily decisive for war?

This can be said with relative accuracy: the finest hour of space infrastructure, apart from the intercontinental missiles that defined the Cold War from the very beginning, was the first Gulf War in 1991/92, when entire armies were led by GPS for the first time. The technology, known as the “Global Positioning System”, was originally purely military. Only later was it used for civilian purposes, like so many other things. And even today, the Americans reserve the right to block GPS for civilian users in the event of a crisis. This is why Europe has made itself independent with the Galileo system.

ACE Aeronautics: „Wir sind Full-Service-Anbieter für den Black Hawk“

And who are the key players in space?

The USA, Russia and China. They are followed by France, Great Britain, Israel, India and Japan. Iran has ambitions, as does Brazil. Europe is fragmented, with only France and, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom having a serious military space structure.

International law is supposed to prevent the use of force. Does it also do this in space?

Rather badly. Although Article 2(4) of the UN Charter prohibits the use of force in international relations, the right of self-defense under Article 51 of the Charter is as full of holes as a Swiss cheese. Every attack is declared a defense. Russia is the prime example. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 allows military activities in space in principle, only the use of weapons of mass destruction is prohibited. This was a ploy by the superpowers: Intercontinental missiles were to be allowed to continue flying. The wording of Article IV of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which is not immediately obvious, can certainly be described as the result of considerable diplomatic wrangling.

So armed space attacks are already conceivable today?

Yes, it is clear under international law that an attack from space can be considered an “armed attack” within the meaning of Article 51 of the UN Charter. This can take place kinetically, i.e. through physical destruction, or non-kinetically, for example through cyber operations. In the latter case, the distinction is blurred. Because if the use of cyber acts like a weapon, cyber is also considered a weapon.

What happens when private companies, such as Starlink or Space X, become militarily relevant?

This is a growing problem. According to Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty, private actors are subject to authorization and supervision. They need a license from the so-called launching state, which remains responsible for their actions. As soon as they actively participate in hostilities, they lose their civilian protected status. They are then considered combatants.

“The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 basically allows military activities in space. That was a ploy by the superpowers: Intercontinental missiles should be allowed to continue flying.”

What about transparency and control?

Bad. According to Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty, every launch must be registered. The wording: “as soon as practicable”. That means: at some point. This registration is intended to ensure transparency; everyone should know what is flying around where. Many countries do not register anything. The correspondingly toothless registration agreement exacerbates the problem. We simply don’t know well enough who or what is active in orbit.

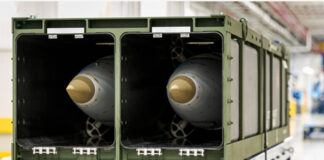

Are anti-satellite weapons permissible under international law?

Formally yes, practically fatal. Anti-satellite tests create debris fields that jeopardize the use of space. The USA, China, Russia and India have recently carried out such ASAT tests. The USA has now committed itself to a moratorium, while China and Russia remain silent. Silence is not consent in international law, but it could indicate that a number of states are becoming increasingly aware of the dangers of these tests.

In your lecture at the Space Symposium, you said that space is becoming the “Theater of War”. Is that more than just a metaphor?

Unfortunately, no. We need to see space as an area of operation on an equal footing with land, sea, air and cyber. The USA has already established a “Space Force”. Germany will have to follow suit, and even smaller European countries such as Austria will not be able to escape this reality. They too will have to develop structures to ensure the protection of their infrastructure in space. Those who ignore this will lose their ability to act.

What could create stability? A new space treaty?

Such a treaty is not realistic because too many large states have no interest in renouncing the possible military use of space. Such projects would therefore fail due to the veto rights of these states in the UN Space Committee. The only realistic option would be a pact between the nuclear states, similar to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Mutual balance is the last remnant of stability we have. Absolute disarmament is illusory.

How likely is an armed conflict in space in the next 20 years?

Not entirely unlikely. The technical requirements have long existed. The legal ones do not. If we do nothing, conflicts in orbit will become just as inevitable as on the ground.

“Austria will not be able to escape this reality and must develop structures to ensure the protection of ITS infrastructure in space.”

And what remains? Hope or resignation?

Neither. I have experienced too many negotiations to be naive, but there are also too many reasons not to give up. I will continue to deal with these issues, even after my retirement. We need education, knowledge and sober honesty about power politics in space. I am convinced that only knowledge can slow down what will otherwise come. I want to play my part in this.

Space as the legacy of mankind. Does that still sound realistic to you?

Yes, as an obligation. International law recognizes the principle of intergenerational responsibility: you must not pass something on to the next generation in a worse condition than you inherited it yourself. This also applies to outer space. It is too valuable to be left to military strategists or those greedy for profit who disregard the environment.

Click here for further news on the topic of world events.