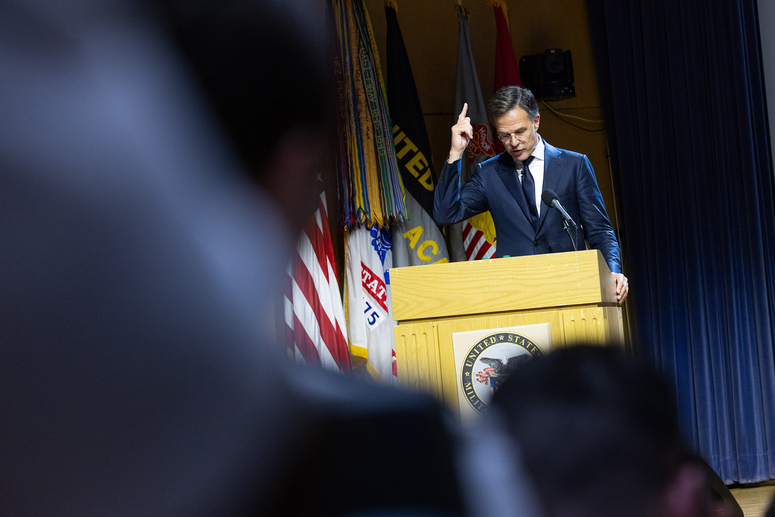

Mark Rutte, former Dutch Prime Minister, has been Secretary General of

NATO

. His path from The Hague to the top of the transatlantic alliance is characterized by crisis experience, pragmatism and an unmistakable style. What makes the NATO chief tick?

There he was again! Shaking hands and making small talk here and there, Mark Rutte recently entered a building belonging to Leiden University in his home town of The Hague. In the auditorium, he answered questions from 750 students, taking a seat on a lectern next to the moderator. You can see his 58 years on his face by now, and yet the NATO Secretary General, one is inclined to say, appeared there exactly as he has liked to present himself in recent years: white shirt with rolled-up sleeves, jeans, black All Star sneakers, rucksack. And, of course, his inevitable grin.

Nickname “Teflon-Mark”

Rutte has now been in his new office for a year. It was clear that this would not be easy in view of the current geopolitical turbulence. Even Rutte, who has attended over 100 EU summits as Dutch Prime Minister, could not have foreseen that the transatlantic alliance and especially its European member states would find themselves in such a spin cycle. And yet, as he answers the first question, he has no regrets about joining NATO: “I enjoy it enormously, it’s a great honor to do this, even if it’s not easy.”

Rutte, who grew up in a reformed Protestant household as the youngest of seven siblings and worked as a Unilever manager before embarking on a political career, knows all about difficult situations. From 2010 to 2024, he headed four successive governments as Prime Minister, and it was two crises that stood out for him personally, as well as in his public image, from these almost 14 years: the downing of the MH17 passenger plane by a Russian missile in July 2014 and the Covid pandemic. Looking back, he himself called the former the “most incisive and emotional event” of his time as prime minister. The beginning of the latter marked the peak of Rutte’s popularity in his own country. The fact that this was followed by a rapid, deep fall shows the strong ambivalence of his political career before he moved on to head NATO.

Rutte, sometimes underestimated at the beginning of his time in The Hague, became the first prime minister of his liberal-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) in 2010 and led it to the most successful period in its history. On the other hand, Rutte’s nickname “Teflon Mark” preceded him because political affairs seemed to simply bounce off him until the magic finally wore off.

At the end of Rutte’s time as prime minister, the child benefit scandal and the disregard for the earthquake victims in the Groningen region caused him great distress. His repeated assertion that he had “no active memory” of the situation in question became a catchphrase and actually made Rutte unacceptable.

In doing so, he did a disservice to the already tarnished reputation of established politics. The growing right-wing populist movement formed the emblematic slogan “Oprutte!” from his name and the verb “oprotten” (to piss off).

What characterized the prime minister during all this time was his uncomplicated joviality. Rutte is more approachable than almost any other politician. Numerous media representatives, employees on company visits or on the street have experienced him as someone who is quick to chat and laugh. He likes to appear at important meetings in The Hague on his bicycle, and as a journalist, Rutte could be asked for a statement spontaneously at public appearances without having to register properly. Even if his staff refused, Rutte would answer.

However, his relationship with right-wing populism was also ambivalent during his record time as head of government. Precisely because he was not a hardliner in his party, one sometimes had the feeling that Rutte wanted to secure support in this spectrum as well. When he then used Eurosceptic or anti-immigration discourse, for example, it could come across as wooden.

“With vision, you should see an ophthalmologist.

"Mark Rutte

He first made the PVV socially acceptable by having it tolerate his first government and then excluded it as a coalition partner. In the meantime, Rutte was a favorite target of right-wing populist Geert Wilders’ tirades.

Rutte, who is a passionate pianist and even flirted with conservatory in his younger years, was also the first prime minister to apologize on behalf of the state and the government for the darkest pages in their history: the failure towards their own Jewish population during the Holocaust, the Dutch role in the transatlantic slave trade and the colonial violence in Indonesia’s war of independence in the late 1940s.

When he put himself forward for the post of NATO Secretary General, this initially came as a surprise. Rutte’s political career has no specialization in defence or foreign policy. In his early days as prime minister, there were huge cuts in the defense budget, and the NATO standard of two percent was only taken seriously in the late phase of the Rutte era, as it was in other member states. On the other hand, he has enormous international experience, unifying capacities and a pragmatic mentality.

Pianist, pragmatist, Protestant

Referring to Helmut-Schmidt (former German Chancellor), Rutte once recommended: “If you have visions, you should see an ophthalmologist.” In his first year, he interpreted his role in exactly the same way: he mediated, moderated and tried to keep everyone on board. Most of all, of course, Donald Trump, whose government has been closer to its transatlantic partners again since the NATO summit in Rutte’s home town in June.

The fact that many found Rutte’s submissive behavior towards Trump ingratiating does not bother him. Repairing the difficult relationship and bringing the national budget towards the required five percent was Rutte’s aim, no more and no less. Mission accomplished. The second year will bring new challenges.

Here

for news about NATO.