In the course of the Second World War the boundaries between the police and the military became completely blurred. Police officers carried out deportations, took part in mass shootings and became part of the extermination apparatus. The exhibition “Hitler’s Executive” shows how state apparatuses of violence can become part of a regime’s service. A visit.

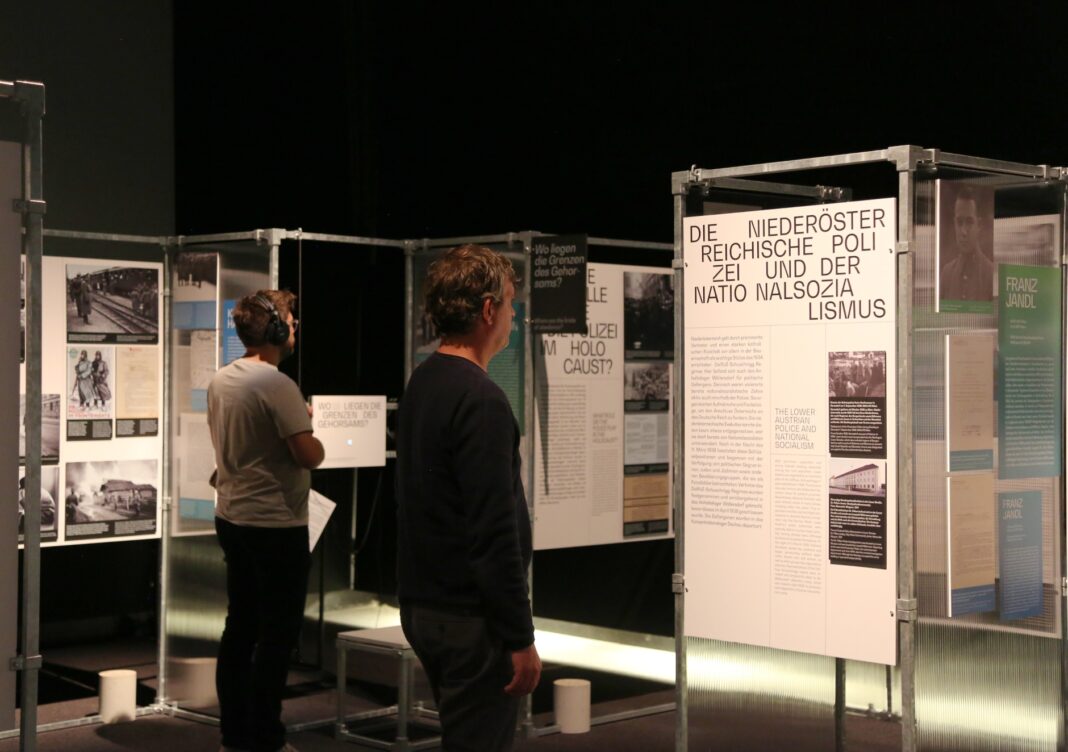

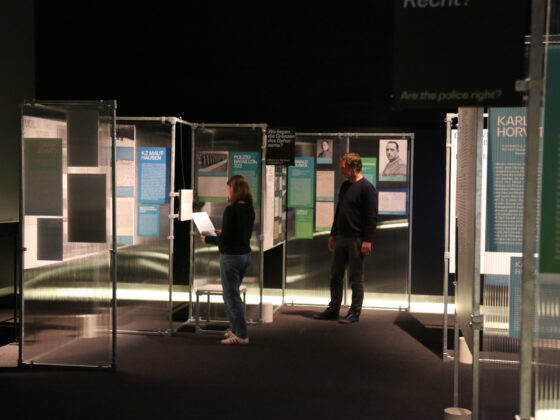

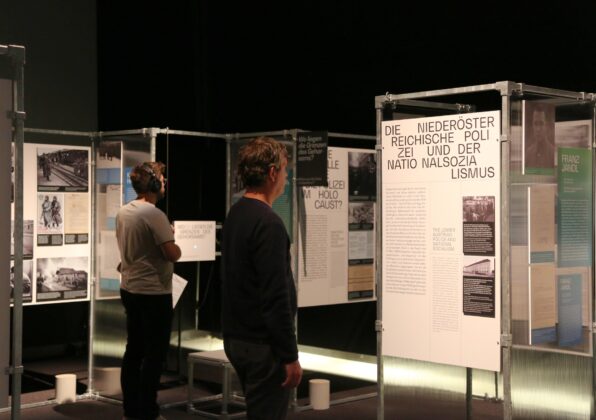

Anyone who visits the traveling exhibition “Hitler’s Executive”, which is on display at the House of History in St. Pölten until February 22, 2026, will quickly understand that this is a topic that goes far beyond the history of one professional group. The documentary shows how easily state apparatuses of violence can be put at the service of a regime when constitutional safeguards come under pressure. For a military audience, it also opens a window onto the question of how organizations that are allowed to use force remain resistant to authoritarian influences.

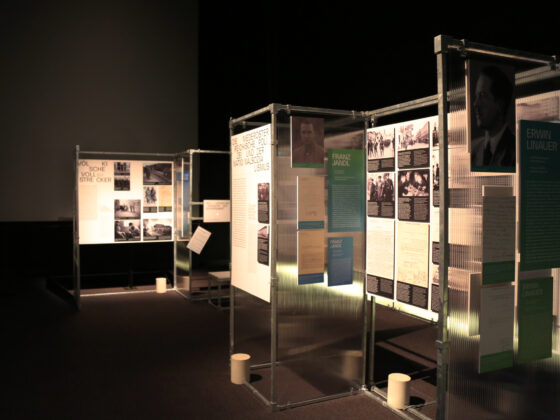

The exhibition was created in 2022 at the University of Graz and the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Research on the Consequences of War after the Ministry of the Interior put out a call for tenders for a corresponding research project. The starting point was debates about right-wing extremist incidents in the police force and the political mandate to systematically come to terms with our own past. The Institute carried out the research project together with the Mauthausen Memorial and the Documentation Archive of Austrian Resistance. Curator Martina Zerovnik developed the concept for the exhibition with the aim of not only collecting scientific findings, but also putting them into a form that can be used in police schools, barracks and educational institutions. Martina Zerovnik says: “This traveling exhibition is also intended to close a gap between research and education.”

“Even during the ‘Anschluss’, key positions in the police force were occupied by National Socialists.

"Curator Martina Zerovnik

The exhibition shows how early state structures can start to slip. A large-format text explains the role of the police in the Holocaust. Below it are sober paragraphs about tasks, official channels and competencies. The language is matter-of-fact, but it leads directly to the images that follow. Two photographs make visible what sounds dry in the administrative files.

One, taken in the Lodz ghetto, shows a group of people standing tightly packed together on the platform. The uniformed police officers in the background appear inconspicuous, almost casual. In the second photo, items of clothing left behind by the victims of the Babyn Yar massacre lie in a ravine. Coats, pants, shoes in a silent landscape that shows how quickly structures turn into deadly routines.

To understand how this came about, the exhibition takes us back to the time before 1938. During the Dollfuss-Schuschnigg dictatorship, the police became increasingly militarized. It acted repressively against political opponents, while at the same time National Socialists infiltrated the organization from within. In 1938, many of the conditions were already in place. Martina Zerovnik describes it like this: “Key positions in the police force were already occupied by National Socialists at the time of the ‘Anschluss’.” Officers who did not conform to the new regime were removed and others moved in. The “Shooting Decree” and comprehensive ideological training further increased the willingness to use violence.

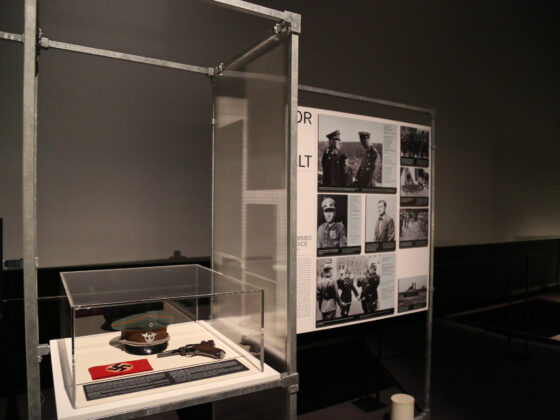

A photograph in the exhibition shows a training situation from this period. Men are standing in a circle, one trainee is lying on the ground. It is a drill that looks like a maneuver. A peaked cap with a Reich eagle badge, a swastika armband and a service pistol lie in a display case. Small objects that illustrate the extent to which symbolism and everyday life merged in those years. The exhibition does not work with overwhelming images, but with sober testimonies that speak for themselves.

As the war progressed, the boundaries between police and military became completely blurred. Police officers became security troops in the rear front area, carried out abductions and were involved in mass shootings. In Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and Serbia, entire village communities were wiped out. Police units were also on duty at Babyn Yar alongside SS and Wehrmacht units. In the exhibition, Zerovnik points out the long-term consequences of this development: “For a long time, the police were primarily concerned with the victims in their organization, but not with their own history as perpetrators.” The difficult return to service after 1945 was facilitated by the fact that the police had never been classified as a criminal organization. Many invoked the need to obey orders. However, Zerovnik emphasizes: “Research knows of no case in which a refusal to carry out mass shootings was punished with death.”

“Research knows of no case in which a refusal to carry out mass shootings was punished with death.

"Curator Martina Zerovnik

The exhibition contrasts these structural developments with individual biographies. The panel on Karl Horvath, a Styrian from a Roma family, is particularly impressive. His life story shows the path from criminalization, forced labour and deportation to his murder in Hartheim. Next to it hangs a private photo: a father with his child on a summer’s day. A picture full of closeness that stands in sharp contrast to the administrative files.

The portrayal of the post-war period also remains clear and unembellished. Johann Lutschinger, a gendarme who had been dismissed because of his Jewish wife, fought after 1945 to come to terms with National Socialist crimes and became a target himself. The careers of Maximilian Grabner, the head of the political department in the Auschwitz concentration camp, and Karl Silberbauer, the officer who arrested Anne Frank, are equally exemplary of the failures of the immediate post-war period.

Bundesheer steigert Leistungsfähigkeit seiner Jagdkommando-Soldaten

At the end, the exhibition poses a question for the present: How can institutions that operate in extreme situations be protected from ideological appropriation? This question is equally relevant for the police and the military. The exhibition shows how important it is for people in uniform to reflect on their role, to know their scope for action and to understand responsibility not as an abstract regulation, but as the core of their profession.

This tour is more than historical education. It is a precise reminder that authority does not create infallibility and that systems can topple if their members do not know where their responsibility begins. The sober presentation gives the exhibition a sharp edge. It leaves us with an awareness that history is not distant and closed, but continues to have an impact on the structures of today.

Click here for further reports from the history section.